|

Typical Bolivian Clothing

Bolivian clothing, dress and hat styles differ by region. Because there are so many cultures and ethnic groups in Bolivia, it’s impossible to speak of “typical Bolivia clothes”. There are at least thirty different typical Bolivian dress styles among the native Bolivian indigenous cultures, each with its own styles for men, women, every day wear, and festivities, including a multitude of costumes, masks and hats.

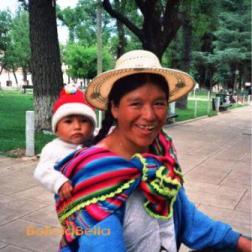

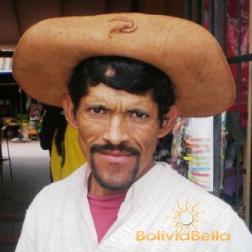

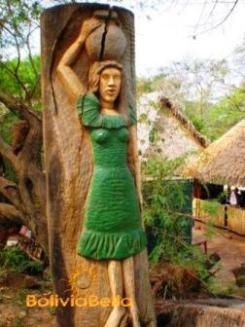

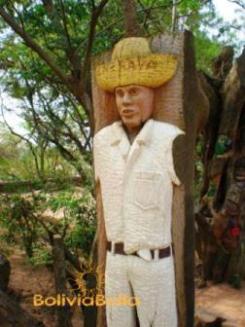

In addition, there are many different Bolivian lifestyles, not only because Bolivia is so culturally heterogeneous, but also because it’s such a large country. Bolivian clothing styles also differ by regional climate and by income levels. And finally, in everyday Bolivia clothes vary simply by choice. Some people enjoy portraying their region’s Bolivian traditions by the way they dress, especially in areas where there are many tourist attractions in Bolivia, while others prefer to follow international fashion trends. Therefore, we’ll describe Bolivian clothes styles in a very general manner according to the regions into which Bolivia is usually divided: Bolivian Clothing: Highlands and ValleysIn the departments of La Paz, Oruro and Potosí, which were conquered by the Incan Empire, typical Bolivian dress didn’t look anything like it does today. The Quechua clothing was colorful but very simple. The women used a rectangular tunic that was long and hung down to their ankles which they tied at the waist with a belt which had pointed ends that hung to one side, down to the middle of the thigh. The men also wore a rectangular tunic, although it was shorter, and used a 'taparrabos' (a strip of cloth used to cover the backside). Both wore “ojotas” (sandals made from strips of leather). During the winter both men and women used a cape which was made out of alpaca fiber among the lower classes and vicuña fiber among the aristocratic classes. The various social classes could be told apart by the colors and fabrics used to make their clothing as well as the way in which they were decorated (with geometric, zoomorphic or anthromorphic embroidered and woven designs). Fine vicuña fiber was reserved for the wealthy while the rest of the population used alpaca, llama or cotton fabric. Lamb’s wool didn’t exist at the time as sheep were brought over by the Spanish. To cover their heads the noble class used 'tocados' (headdresses) decorated with gold, gems and feathers and fine fleece earflaps. The lower noble classes used an embroidered chulo (woven winter cap) with earflaps as a symbol of social status, while the common classes didn’t wear head covering or hats at all. (Today Bolivian hats and hat styles still indicate which region of the country a person is from). The women didn’t use any adornment in their hair and simply parted it down the middle and tied it into a long braid that fell loosely down the back. Sometimes they covered their heads with a mantilla (shawl) or a headdress that was much simpler than what men used, and only if they were members of the nobility. This changed when the Spanish arrived to colonize South America. The Catholic Church insisted upon deciding what was right or wrong to wear among the indigenous population and many of their customs and traditions were disallowed, including their typical clothing. Thus, as of the 16th Century, the Spanish imposed a new style of dress upon the indigenous and mestizo (mixed race) population forcing them to wear the typical European clothing of the era, permitting just a few adaptations to local customs and climate. This is the Bolivian clothing you see “cholas” wearing in the Bolivian Andean highland region today. You can see this in the photos above and below. The word "chola" stems from the word “chula”. In Spain bullfighters had assistants called “chulos” and their wives were called “chulas”. They wore long pleated skirts, a lacey or embroidered blouse, a shawl and booties. Clothing used by other Spanish women was similar with long, pleated skirts, with a 'miriñaque' (bustle) underneath to hold up the heavy skirts, embroidery along the collars and wrists, and shawls draped over the shoulders or head. The men used 'calzas' (pants), and a 'jubón' (a short jacket) over their shirts, a cape, a wide-brimmed hat adorned with a feather, and leather boots that covered their legs all the way up to the middle of the thigh. All of this was copied by the indigenous population, and over time, they adopted these as their own typical Bolivian clothes, and still wear them today. A few changes have been made, however. It’s interesting to observe that the “chola’s” Bolivian dress style varies from one state to another. For example the “pollera” (the pleated skirt) in La Paz is long, reaching down to the ankles and very voluminous, whereas in Cochabamba and nearby Chuquisaca they are less voluminous and only down to the knees, and in Tarija the pollera is shorter than anywhere else. The same can be said about Bolivian hats. In La Paz hats are of a “bombin” style; in Cochabamba they are high and rectangular, with a midsized brim; and in Tarija they have wide brims, a low height and slightly elevated rims. Lastly, there are differences in the mantilla (shawl): in La Paz the manta is thick and usually of only one color, pinned together in the front with a long stick pin or very large safety pin. In Cochabamba and Tarija cholas use smaller shawls that are not as heavy, usually embroidered with flowers or other designs, and hemmed with fringe. Cholas in La Paz used to wear European ankle boots but now use a flat shoe with a rounded toe, while in Cochabamba they used ankle boots when it was cold and sandals when it was hot. In Tarija the women and men both used “abarcas” (flat sandals made from leather or rubber). What is most similar in the Bolivian clothing used by cholas is the blouse which is usually lacy and can be either short or long-sleeved, according to the climate of the region, but isn't very different in any other way. Bolivian clothes are different in Potosí and Chuquisaca where, although the chola costume is sometimes used and adapted to the local culture, it isn’t truly representative of these two departments. Typical clothing in Potosí does still somewhat hail back to what the Incan Empire imposed in this area, as women use a long woolen tunic and their skirts are not wide or bell-shaped. These are almost always made of lamb’s wool or llama and alpaca fibers, died black, and have geometric designs embroidered around the bottom hem of the skirt, on the collar and on the wrists and the tunic is tied at the waist with a faja (wide belt) similar to that used by the Incan women, which is usually red. This is complemented by a cape of the same color with adornment along the borders, abarcas for shoes, and a very short-brimmed hat in the shape of a bowl, surrounded by a leather tie. Men use straight pants, usually of a raw fiber or black color, a rectangular shirt (long or short-sleeved, according to the weather), also of a raw fiber color and made of wool, and a very colorful belt around their waists. The abarca is also their typical shoe and they wear a chulo (a knit cap with ear coverings) usually woven with geometric, zoomorphic or anthromorphic designs. Women carry their children, food, market produce and anything else they need to carry on their backs, wrapped in an aguayo, a very colorful woven sling made from woven fabric. Cholas in La Paz do too. Typical Bolivian clothing in Chuquisaca is similar to what is used in Potosí, with variations only in the patterns with which the clothing is adorned, the weaving style, and the hat with is similar to a three-cornered hat with many colorful embroidered adornments, predominantly in red and ochre colors, with ribbons hanging from them. The radical difference can be seen in the men’s clothing as indigenous men from Chuquisaca use a very wide-legged straight pant that is cut short slightly below the knee, and a wool shirt under a colorful poncho with multicolored horizontal stripes. Their abarcas have a very thick, or high, sole with spurs (copied from the spurs worn by Spaniards when they rode horses), and theirs are the most interesting of all Bolivian hats, which resemble the Spanish iron armor helmet used by the Spanish conquerors. In each of these five states, the women continue to wear the typcial clothing, such as belled skirts, hats and shawls daily in both rural and urban areas of La Paz, Cochabamba, and Tarija (as well as other regions of the country to which they have migrated). However, the men use their typical clothing only during festivities, religious indigenous ceremonies, dances, carnaval, and other events, preferring to wear slacks, buttoned shirts, sweaters or sweater vests, and suit coats on normal days. The exception to this might be areas where there is much tourist activities, such as in the city of Sucre where you can observe the “Tarabuco” men wearing their typical costumes and Spanish-helmet style hats as they sell handcrafts and woven fabrics in the city center. Bolivian Clothing: Lowlands and ChacoPrior to the colonial era, the tribes that inhabited the tropical Eastern Bolivian plains and southern region didn’t wear much clothing at all. Some women wore triangular pieces of cloth over their backsides made from feathers of cotton fiber while men wore a sort of sheath or 'carcaj' to cover their groin area and even then, only boys over 14 years of age wore them. Both men and women wore their hair loosely and adorned themselves with necklaces made from bones and seeds, feathers, animal teeth, or flowers (the women). Most didn’t wear shoes. Some tribes pierced their lips or ears and adorned them with bones or rods. When it was cold they used animal fur for covering. Only tribal chiefs used feather head covering. What is today considered to be their "typical" Bolivian clothing was imposed upon them by the Jesuit priests that arrived from Europe to evangelize the region as the other conquistadors didn’t dare challenge the nomadic tribes (and in addition, there was no gold or silver in this region). As of the 17th Century, when the first indigenous reservations were created and directed by the Church in the areas of Moxos and Chiquitos (in the departments of Beni and Santa Cruz, respectively) and in the Chaco region (which covers portions of Santa Cruz, Chuquisaca and Tarija) the Jesuits took it upon themselves to dress the indigenous people. The clothing chosen involved a long, sleeveless, cream-colored cotton tunic that reached to the ankles. They wore “abarcas” on their feet and the men were obligated to cut their hair in the “mushroom” style so often seen in pictures and drawings of the era (like the Franciscan and Dominican priests, only without the tonsure). Women were forced to braid their hair in one or two braids and could use no other adornment other than a necklace with a cross or a flower in their hair when festivities allowed. This style of Bolivian clothing persisted until modern times, although it eventually evolved and became more colorful. The somber women's tunic became a dress to which colorful ribbons and a frilled collar were added and the dull raw natural cotton color was replaced with strong colors. Cotton was complemented with other thin, light fabrics due to the hot tropical climate. Men began to use wide-cut pants and shirts, invariably of light-colored cotton, and a hat made from woven palm fronds called a “saó”. This style is typical of Eastern Bolivia and is still used during festivities or at tourist attractions. The women’s dress, known as the “tipoy” or “tipoi” (see photo above) is another example of Bolivian cultural diversity because, although it is commonly used in the departments of Beni, Pando, Santa Cruz, and portions of Tarija, the style wasn’t exactly the same in every one of these areas. The differences are not very notorious, but an attentive person would notice that the tipoy from Beni has a wider, belled skirt and the frills along the neck are a bit longer and more voluminous, while the tipoy in Santa Cruz is straighter and more tubular and slightly more body-hugging with smaller frills. The tipoy in the Chaco region is very loose, without a very defined cut and is basically a rectangular, sleeveless tunic with ribbons for adornment. As to accessories, in the Chaco region they use necklaces made from seeds and bones and a braided bun in their hair, while further north it is customary to use a long loose braid down the back, which may or may not be adorned with flowers. In the Chaco region another type of traditional Bolivian clothing persists, and it isn’t of Bolivian origin at all. It also was not sed among the indigenous men and women, only those of European descent. The women wore a dress similar to that of the flamenco dancers in Spain: a very full bell-shaped skirt all the way down to the floor with a short sleeveless blouse, just to the waist that has frills on the neck. Sometimes it’s a single-piece dress. The men wore “bombachas”, a very wide balloon-legged pant closed at the waist with a strip of crossed leather similar to a shoelace, with the pant legs tucked into a pair of high and very pointed boots, with a low heel. They wore very wide hats with the front flap folded upward and tied with a leather cord. The above is what is now known as traditional Bolivian clothing; however, today Bolivians normally use the same clothing worn in the Western world and the typical clothes are used only during festivities. The one exception to this, as mentioned above, are the cholas of Western Andean Bolivia who continue to wear their full, pleated skirts, shawls and hats on a daily basis as they have for several hundred years. In addition, this is just a summary of the most representative typical Bolivian clothing. There are really 36 native cultures in Bolivia and each has its own typical style of clothing and accessories. To see many more you’d have to attend the many Bolivian festivals and other events that showcase Bolivian traditions. The largest of these are: the Carnaval de Oruro, which features costumes representative of numerous points in the history of Bolivia, and Carnaval in Santa Cruz, the Gran Poder festival in La Paz, the Urkupiña festival in Cochabamba, and other such as the Ch’utillos and Guadalupe festivals. Attending one of these is enough to satisfy curiosity as the parade of typical Bolivian clothing styles is like a colorful party. Bolivian Clothing: Santa Cruz and TarijaThe first two pictures are of two wood carvings found near the Pirai River in the city of Santa Cruz. They depict the typical Bolivian clothing used by "cambas" which is the name given to people who live in the department of Santa Cruz. The woman is wearing the tipoy described above, and the man is wearing the typical Bolivian dress style for men with the wide-cut pants and "sao" straw hat. Of course people only dress like this for festivities and special occasions now or when they put on a show for tourists, as the men in the third picture below are doing. You can see them at nighttime at the central plaza in Santa Cruz as they play typical Bolivian music of Santa Cruz. The fourth picture depicts the typical Bolivian hats worn by men in Tarija. Many men still wear them daily.     |