|

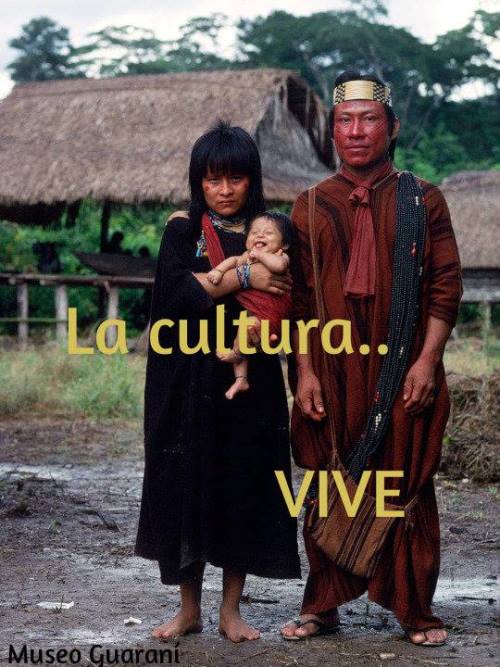

The Tupi Guarani Culture of Bolivia I traveled to Tupi territory in extreme Southeastern Bolivia in April of 2009. My trip began with a long 12-hour bus ride from Santa Cruz to Charagua, then on to Isiporenda where I spent the night with a Tupi family. The next day we traveled by road to the heart of their territory stopping at each small town we passed along the way to learn about their culture.

The Guarani people are warm and inviting and hospitable and very friendly. At each town they showed us their small businesses such as beekeeping, small coffee and cocoa production facilities, their small farms and fields, irrigation systems, unions of women weavers, and more. We visited their homes and school until at nightfall we reached La Brecha, the largest and central town of the Guarani. Here we spent the night. There is no electricity here after dusk and meals are prepared over open fires or in clay or brick ovens outside. Outhouses consist of holes in the ground and the night air was filled with the bleating of hundreds of goats who gathered in the central plaza as soon as the sun went down.

Early the next morning we visited the homes of some of the local women who weave. They've formed a small cooperative and share both expenses and profits (about $130 divided between all of them for an entire year's work). They showed us how they spin wool into yarn, dye it, and set up their looms. It takes 3-4 months, many hours a day to weave ONE hammock which typically sells for about $50 or $60 dollars in the city. Other women in nearby towns are beekeepers and still others grind, roast and package both coffee and cocoa made from a local bean-like plant that has a rather chocolaty flavor. Nearly all families have a small rice field which is for their own consumption. The men leave early in the morning to go hunting (usually for wild pigs or other local fauna) while the women leave to hand-pick rice, which is then dried on a burlap sack in the sun for the family's daily meal. Older children and grandmothers watch toddlers and babies while parents work in the fields. At night the men go fishing in the river in the pitch dark. Sometimes, if they're lucky, there is fish for breakfast. Fruit and vegetables are not a big part of the diet here, although there were tangerines and lemons, as well as chirimoya in some parts. This area of Bolivia is arid and hot and only gets substantial amounts of rainfall during the rainy season when roads become a mass of thick reddish clay and mud and transportation between this area and major cities is extremely difficult. We were given the chance to visit with the Gran Capitán of the Guarani who welcomed us into his meager home and promptly brought out a 40-year old photo of himself and a past Bolivian president. Most of the conversation centered on how the Guarani have struggled to be included in the national political process. This area of Bolivia has traditionally been all but forgotten for the past 400 years, the Guarani not being as numerous or important as the Aymara and therefore politically, all but ignored although they are the third largest ethnic group in Bolivia. Throughout the area the extreme poverty was evident in everything from the almost complete absence of vehicles (with the exception of ours and 2 buses that run through the area 3 times a week) to the lack of water and latrines, to the lack of fruit and vegetables, to the condition of the homes and schools. It is evident this area has not been visit by many authorities although the Guarani did mention that occasionally a tourist or NGO worker will spend a few days there. The La Brecha hospital serves all nearby villages and the Isiporenda Clinic, several hours away, serves another few local villages. Neither hospital has electricity at night and must use generators. Emergency services don't truly exist. There are no ambulances or vehicles of any kind for transport either. Despite this, the Guarani are always smiling! They are among the most hospitable people I have met anywhere in Bolivia. The children were bright and playful and cheerful. The men and women opened their homes to us (there are no tourist facilities here) and shared meals, conversation, candles and anything else we needed. Their abundant hospitality is also evident in the relationships they have with the very large nearby Mennonite colonies. The tall, mostly blond and blue-eyed Germanic Mennonites (many from Mexico and Paraguay) offer a stark contrast to their Guarani neighbors physically but also in terms of the development of their colonies. Their homes, each surrounded by fields, are large and well-built, and all of a single design, not unlike the tracts of mass-manufactured identical homes in North American suburbs. The difference is that they build their homes with their own hands and they have no modern plumbing and no electricity. Several large colonies of Mennonites (numbering in the hundreds of families) have settled in this area (within Guarani territory) and have purchased large tracts of land from the Guarani, who have welcomed them with open arms. They have huge farms and large fields as well as herds of cattle, butcher shops, a cheese factory, and stores. The Mennonites use no electricity or vehicles, preferring horse-drawn carts. They also do not own phones or cellular phones and they live off the land completely. Once a week some of the Mennonite men or families travel the 12 hours to Santa Cruz to sell their goods (mostly meats, cheeses and jams) to stores in the city, although in Santa Cruz you can also see many of them selling in streets, weaving between cars at stoplights. They are very very organized, disciplined and strict. They speak a dialect of German and Spanish. Their children are home-schooled or attend Mennonite schools. The members of the colonies are not allowed to date or marry outside the Mennonite population. They are typically a very closed society which made their openness to our visit and the absolutely fun time we shared, very surprising. We visited the Mennonite colony of Durango and their cheese factory and were given a rare glimpse into how their lives revolve around the fruit of their labor. We also visited their butcher shop and a local store in Isiporenda. It was an unexpected and surprising visit. Visitors are not usually afforded this privilege but we were given this opportunity because our Guarani guide has an excellent relationship with the Mennonites. The Guarani and Mennonites have a really good relationship and it is evident they show mutual respect. But they are also very friendly and open with each other. Some of the Guarani work with the Mennonites, most shop at their small grocery store, and in general the two populations are completely cooperative with each other. They share tools and information, give each other rides, and help each other with repairs and maintenance. It was wonderful to see how well these two completely different cultures worked so well together. We returned to Charagua to take the long bus ride back to Santa Cruz after four days in the dust and heat in one of the most remote areas of Bolivia. I left promising to meet with Guarani leaders, at their request, to show them my photos and help them put together on a proposal for the national government. They want to open their territory to tourism and need the government to fund facilities, roads, water mains and electricity. They know that opening the area to tourism will mean the government will finally have to develop this area and fund the basic services they need and that this may be the only way to achieve this. Their territory, which borders on, and includes part of Kaa Iya National Park, has yet to be developed and this part of Bolivia is rarely included in the national budget. In order to give you more statistical information on the Guarani, who have inhabited the area now known as Bolivia for over 2500 years, the following portion of this article contains excerpts that have been translated from (and can be found in Spanish at) this site: www.prodiversitas.bioetica.org/tupi.htm

Origin and Geographic Distribution The peoples of the Arawak language family, a linguistic family that extends throughout the Amazon, Orinoco, Antilles, and Northern Colombia, settled in the region known today as Bolivia and Argentina about 2500 years ago. They occupied the western region of the Gran Chaco and parts of the provinces of Salta and Jujuy. They were defeated by the Guarani (also known as Chiriguanos, in Quechua), who arrived in this region between the 13th and 14th centuries. The Guarani (Chiriguanos) subjugated the Arawak peoples making them “minor partners”, and changed their name to Chané. The families of both peoples developed a peculiar way of living together calling themselves the Tupi Guarani (although in literature they are more commonly referred to by their Quechan name: Chiriguano-Chané). The Legend Tupi Guarani history states that two brothers, Tupí and Guaraní, were traveling these regions with their wives and families until disputes between the two women caused them to go their separate ways. Thus Guaraní headed East. The peoples now known as Guaranís in Paraguay, Northwest Argentina and southern Brazil originated from his family. Tupí headed West, establishing his family in what is now Bolivia, in northwestern Argentina, northern Chile and southern Perú. Political Organization They had a political organization in which men did all the decision-making with a Chief and Council of “Ancianos” (Elders). Families owned private property (for gardens and produce) and there were also collective properties for community work and use (called “mingas” or “motiros”). Large community houses called “malocas” were built form tree trunks and stray, as were barns. Economy The Guarani branch of the family preferred hunting and warring, leaving the Arawak families to do the cultivating and to work as artisans. Guarani became their common language, although over time, there is evidence their languages mixed. The Arawak practiced horticulture, rotating crops and using fertilizer. They produced corn, manioc, peanuts, yams, cotton and beans. They also raised herds of llamas. They used bows and arrows to hunt, as well as traps, and used nets and arrows to fish. They were well-versed in working silver and gold, making pottery, wood carving, and had a small textile industry. The Guaraní cultivated manioc, corn, tobacco, cotton, and vegetables and used slash-and-burn methods of clearing the jungle to use the land for crops. They were skilled warriors and hunted with bows and arrows. They used many fishing techniques using bait and tackle, spears, nets, and traps. Cosmology When the taperigua plant (Cassia carnavalis) blooms, the Tupí Guaraní begin a time of celebration called the “Arete” which continued until the blooms withered. This was an agricultural ritual that took place when the abatí (corn) began to ripen, which they used to make “kanwi” – known in Spanish as “chicha” (an alcoholic corn meal beverage). The women would prepare great quantities of kanwi and would make themselves a new dress “mandu” or “tipoy” and would look for uruku seeds which they used to paint their cheeks red during the “Arete” Festival. The Chief (also called a Captain) would initiate the festivities. They would wear masks (aña añas) and play musical instruments as they danced toward the groupings of houses, led by one person carrying a stick adorned with taperigua flowers. They would drink from the vessels containing kanwi, their ritual beverage and dance in rows or circles in mixed groups of men and women, adults and children. The presence of Europeans in the area seems to have led to a change in the dates of this festival from August to February. Along with the conquistadors and colonists, missionaries arrived (often before them, in order to facilitate domination) and soon the festival dates were changed to coincide with the European “carnaval”. This may have also led to them to abandon the tradition of orgies. Masks Inspired by the Arawak, the tradition of making and using masks still exists. The use, by men, of ritual masks is one of the most outstanding features of the Arete festival. Men, especially the young men, would go into forest to look for “samóu”, a wood also called “yuchán” or “palo borracho”, with which they made their masks. Their masks depicting animals are especially realistic. The most common are parrots, toucans, dogs, deer, tapirs, jaguars, pumas, monkeys, and now also bulls, horses, and goats. They also made masks of human faces. Music Music groups played the pieces to which they danced during the festival and also danced as they played. The instruments they most commonly use are: Temïmbi – a type of flute generally made of sugarcane, but now also of metal. Pin Pin – a type of small drum Ungúa – drums that look like the wooden mortars used to grind corn Basket Weaving Although some women weave, it is primarily the men who used plants to weave baskets and other items. They usually use the “caranday” palm (also called black palm), but they have to travel far to find them. They also used a hollow reed called the “tankuaransi” to make baskets. They make hats, baskets, mats, chairs, and other items and sell them in the local market. They are also used to barter with other neighboring communities. They also make pottery, although this is exclusively a job for the women. Their Current Situation In 1986 there were 18,000 known Tupí Guaraní (both Arawak and Guaraní) in Bolivia. Most of them work on haciendas, in sawmills, and live on borrowed or rented land. A few work for oil companies, some road construction companies, and some hydroelectric companies. Some inhabit government land that has not yet definitively been declared theirs. They still use their own language, Guaraní, but at the schools they attend only Spanish is spoken and because of this, and their state of malnutrition, many don’t advance much in their studies.

|